Two-Years Enlistment, & I Met General Grant

So many people contributed to me having an amazing experience that I wanted to write about it (and here we are!).

A huge reason for me going to the 160th Battle of Shiloh Reenactment is that I wrote a book with characters who join the 53rd Ohio Infantry; they were among the first units to engage with Rebel forces and held their ground gallantly to create an orderly withdrawal (and save the army from routing).

As a writer, experiences are everything — it’s the only way to gain sensory details, i.e., smell and touch, that make stories stronger. So by going to this event (and others), it’s giving me crucial experience that’s as authentic as I’ll ever get to the actual Civil War. So embarking on this trip was a valuable learning experience. But it wasn’t all work; it was damn good fun, too.

When embarking on a road trip, finding the right companion makes a world of difference. I couldn’t have asked for one better than Mel Jackson-Hunter (and as I like to say: she can out march, drill, and shoot any man). After a 13-hour drive from Northeast Florida, we arrived Thursday evening with enough time to register and set up camp with the 66th Ohio. This group was patched together with units from Ohio down to Florida, forming a formidable force.

Roaring fires sparking up throughout the area always signal the event is underway. The camp is a special time of meals, good conversations, and the school of a soldier. So we gathered wood, collected water, cooked, and cleaned dishes. Cleaning our weapons ensured their safety, and we inspected our cartridge boxes to make sure we had an adequate amount for the days ahead. The reenacting battlefield was actually part of the actual battle’s outskirts, so there was a special connection picturing how the soldiers may have been doing the exact same actions we were 160 years prior.

Reveille sounded before dawn, so morning inspection came with candles. A surprisingly chilly morning nipped at our noses — but we stood at attention nonetheless. The soldiers readied out to the field for a reenactor-only skirmish. These bouts are helpful for those rusty in the School of a Soldier. It allowed the 66th Ohio to practice firing:

By rank

In a full line at the same time

By front rank then rear rank

By file

Like a domino effect, it’s continuous firing from the right file down the line to the left

Soldiers on the right will have reloaded by the time the last person on the left fires

Rebel units continuously pouring out from the trees struck me; it reminded me of the actual battle. The Confederates stretched across the open field, pushing us back as the day drug on. We ceded our position, reenacting the withdrawal. Halfway through was when I took a hit.

There’s an art to “dying” in a reenactment, which I’m thrilled to practice if I see the opportunity. One must visualize where the bullet lands and ask whether it’s a direct hit or, more likely, a wound. If it’s a wound, you need to think about how the injury affects you to mimic a realistic response.

The battlefield opened its fields to spectators on Saturday, when the Hornet’s Nest was planned to be reenacted. Dozens of Confederate artillery lit up, extending from the spectator line across the field and to the tree line. They pummeled the Union infantry to withdraw across the field.

Rebel cavalry swooped in to turn the withdraw into a route, but the mounted men in blue held them back. Federal guns answered the Johnny Rebs once the infantry had cleared their line of fire and found cover. Of course, the protective cover would be merely decoration for actual soldiers of the time, but spectator visibility was a more crucial objective.

The Confederate forces then advanced both through the trees and across the road. They reformed their lines and advanced on the Union. Both sides prepared to take the battle to the bloody end. The next expected maneuver would have been for the Confederates to surround Union forces, capturing them to reenact Gen. Benjamin M. Prentiss’ surrender at Hornet’s Nest. Much to the soldiers’ disappointment, the engagement was called to an early halt.

Luckily, our spirits weren’t dampened for long as Grant came to rally the troops for the next day. With rest and a prayer for salvation, we carried on! Sunday was dedicated to reenacting the Union counterattack with Buell’s reinforcements giving us the edge. So though we were battered, we were ready to give ‘em hell.

(Photo left to right: Dante Parenti | Ehron Ostendorf | Mel Jackson-Hunter).

The soldiers gathered to drill in the morning, reviewing maneuvers, calls, and orders. Thanks to Evan Phillips, the 66th Ohio came to the field a disciplined and spirited team. We put the Johnny Rebs to shame with crisp lines of fire, keeping a steady rate while advancing on the enemy. The general arrived to outline our objective — push the field and turn the Rebel guns back on them. Most importantly — don’t give them an inch. We held our ground, pressing the enemy back onto themselves until they fled.

Reconnecting to the Past

A few final notes are that I loved going through the national battlefield afterward with Mel; I had been there previously but had not seen the actual sights thoroughly. We had conversations with interesting people, saw a note left from the Waterloo descendants on an American flag, and walked the grounds where both sides had lost many.

We also hopped across the river to see the house that served as General Grant’s headquarters in Savannah and accidentally met the man who it! There was a plaque of information, so we guessed it was public property. Ironically, a car rolled down the street at that moment — “I hope that isn’t the owner,” I said to Mel. “That’d be funny,” Mel responded. “What are you doing?!” the man asked. Luckily, he understood that we were reenactor tourists and was quite pleasant — I also felt awful for invading his space, but we couldn’t pass up the opportunity with a 13-hour drive ahead of us.

Special thanks to…

And a huge thank you to Emily Foxx, Dante Parenti, and Mel Jackson-Hunter for providing many amazing photos and videos you see here 💕 especially the visually stunning photos from DavisonImages.com.

Fuzzy on the details of the Battle of Shiloh? Read below!

Battle of Shiloh Summary

The battle of Shiloh (Pittsburgh Landing) was the bloodiest engagement of the American Civil War up to that point, with nearly twice as many casualties as all previous major battles of the war combined. This was a battle of multiple surprises and attempts to outmaneuver the other across fields and through thicket. The Union army’s plans were to move against Corinth, MS, once Major General Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Tennessee conjoined with Major General Don Carlos Buell’s Army of Ohio. Grant’s forces camped and drilled at Pittsburg Landing to prepare for their next engagement.

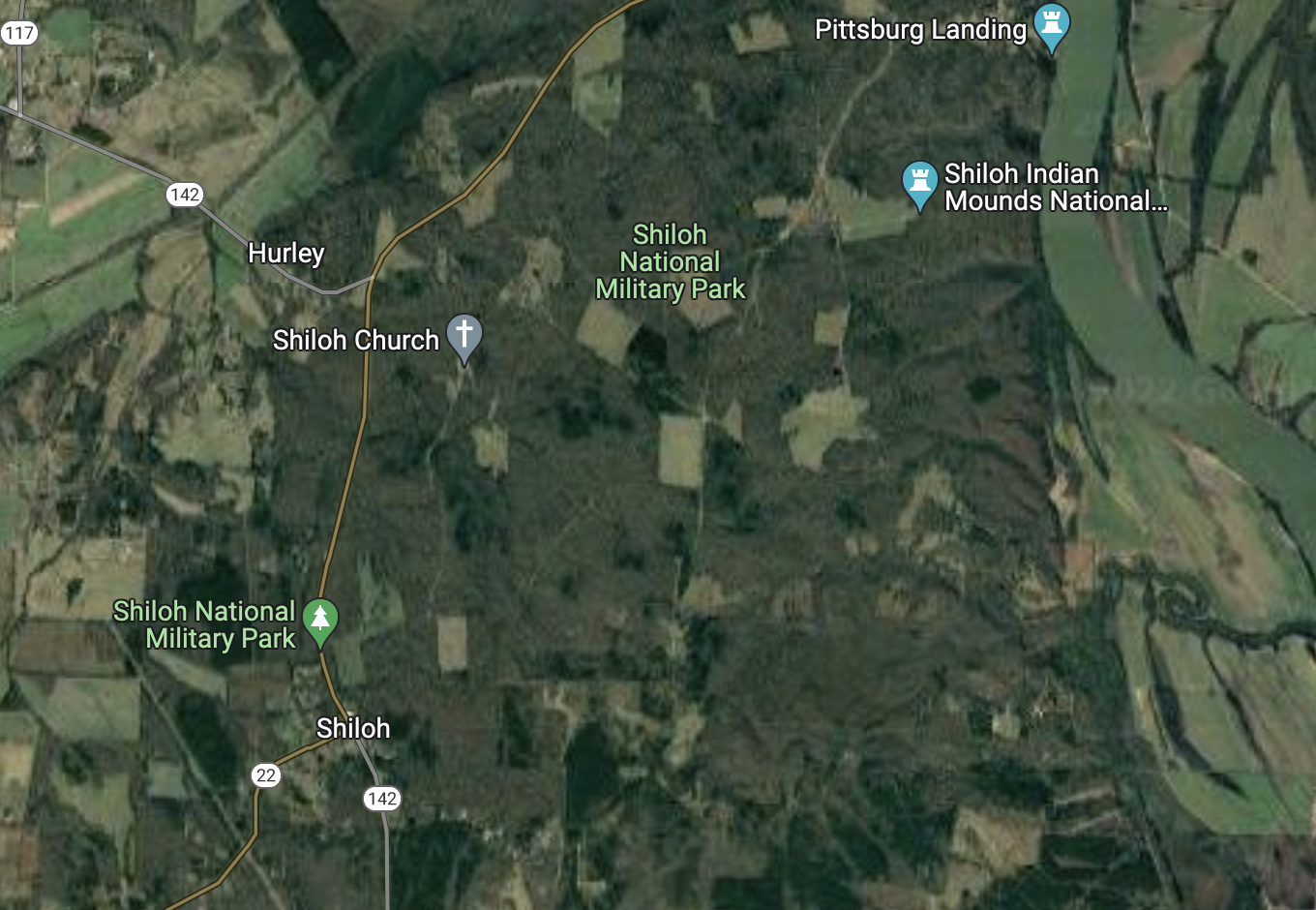

Satellite imagery of Shiloh, TN.

Knowing where the Union had set its sights, General Albert Sidney Johnston directed his 44,000-strong Army of Mississippi to exploit this opportunity. They aimed to hit the unsuspecting Federals before they could receive reinforcements. This strategy would cripple Union war efforts in the western theater and add much-needed morale after a recent string of Union victories (Belmont, Fort Henry, and Fort Donelson).

Gen. Johnston orders his soldiers forward on April 3, but a downpour caused them delay. For history lovers, this tends to be a foreboding sign like the rains that added to Napoleon’s downfall at Waterloo. But striking at the Federals before they strengthened their numbers was all too evident with preemptive skirmishing after dusk on April 5. The landscape then as much as now forms a puzzle of small, open fields and dense thicket. So the men rationalized that the sound of gunfire must be coming from other units within their army who were hunting.

“Take your damned regiment back to Ohio. There is no enemy closer than Corinth.”

— Union General William T. Sherman

Interestingly enough, Sherman was put in command in 1861 to oversee Kentucky (a “border state,” or a neutral state). The pressures of command weighed heavily on him, fueling his overestimation of Confederate strength and calling for reinforcements enough times that Washington replaced him with Buell. This lent to his lax position at Shiloh, which is evident in a letter to his wife, where he explained that if he took more precautions, “they'd call me crazy again.”

By the morning of April 6, Confederate infantry poured from the woods, surprising the Federal’s southern camps. Fighting ensued around Shiloh Church as the Confederates pushed the Union back — but the boys in blue counterattacked, holding their ground in order to withdraw in an orderly fashion. Sherman’s ability to think on his feet allowed the troops to reorganize and not lose hope.

Exterior of reconstructed Shiloh Church

Interior of reconstructed Shiloh Church

“Well, Grant, we’ve had the devil’s own day, haven’t we?”

— Sherman.

“Yep. Lick ‘em tomorrow, though.”

— General Ulysses S. Grant.

The stoic rock the army needed him to be, Grant formed defensive positions at:

Shiloh Church

Peach Orchar

Water Oaks Pond

Sunken Road — later to be known as the dreaded “Hornets’ Nest”

A stone’s throw away at the other side of the battlelines, Confederate General Johnston takes a bullet in his right knee.

“General, are you wounded?”

— Harris

“Yes... and I fear seriously.”

— Johnston

The general had a tourniquet in his pocket, but sadly, his personal doctor was not there to apply it. Why? Because Johnston had ordered his personal doctor to aid captured Union soldiers. This admirable act left the Confederate commander to bleed to death, leaving Gen. Pierre G. T. Beauregard to take command.

Beauregard pressed the attack, unaware that Buell had already arrived with reinforcements for Grant overnight. The Union army grew to 54,000 near Pittsburgh Landing, outnumbering Beauregard’s force of 30,000.

April 7 saw Grant strike back, forcing Confederates to fall back and regroup, but Beauregard ordered a second counterattack. The Confederate right flank was jeopardized with naval artillery support from the timber clads USS Tyler and USS Lexington. As the Confederates and Federals tore at each other, the battle turned into a stalemate. Knowing he was outnumbered, the Confederate commander ordered a withdrawal and retreated toward Corinth.